This article by Teresa Grøtan is reproduced with permission from The Kavli Trust, which provided major support for HDI’s work in Niger to protect women’s lives and dignity from 2009–2021. Photos © Health and Development International

Work to improve the public’s health in the countryside of Norway and Niger is not as different as one would think, according to physician Anders Seim. For the seventh year in a row he is receiving support from The Kavli Trust to prevent the consequences of blocked childbirth in Niger.

– A series of coincidences.

That is how he describes it, the reason he became involved with health issues in a completely different part of the world than home in the countryside at Fagerstrand.

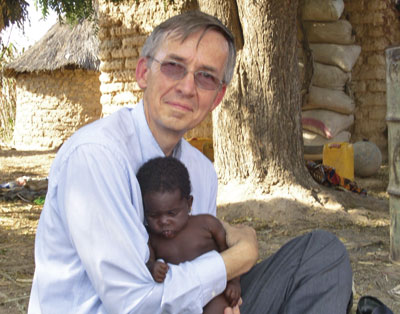

Dr. Anders Seim. Photo © Health and Development International

Anders Seim has always been intrigued by public health. It is about observing, seeing that something is not as it should be, and exploring whether it is possible to do something about it. He speaks of the doctor in Finnmark, the very north of Norway, who noticed that people who had the coffee grounds boiling all day seemed to have more heart attacks. Could there be a connection? And the doctor in London who stopped the cholera epidemic because he asked himself: What is going on here, and what can we do about it?

Guinea Worm

An interest in public health has driven his work both in Norway and Niger. The difference, he explains, is that issues are typically more dramatic in Niger, so it is easier to see whether interventions put in place make any difference.

The story of how he became involved with his first big project, he explains as follows:

– I was a country doctor in Norway and travelled to the States to take a public health degree. Computers were beginning to become available – this was 1987 – and I was on my way down into a basement at the university to use the computer lab. In the hallway I met an Ethiopian classmate who mentioned a guest lecture that was about to start right there. One cannot turn down an invitation like that, so I went and listened to Dr. Donald Hopkins who had headed the CDC (US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) talk about Guinea worm and efforts to combat it. One had known how to get rid of Guinea worm for 100 years but not envisioned it was really possible to eradicate a disease until they actually succeeded to eradicate smallpox. But they needed funding. I thought this must be right up the alley for what Norway likes to do. It was a silly idea, but that’s what I thought. And so I started working on Guinea worm eradication while also working as a country doctor at Fagerstrand.

At that time, in the mid 1980s, 3.5 million people in 22 countries suffered painfully because of Guinea worm disease. The worm can be a metre long and pushes its way out through the skin of its host, a person. The disease comes with contaminated drinking water.

Filter Straws

For a year’s time, Anders knocked on doors at various organizations he thought might imagine working on Guinea worm. He finally realised none were ready to do so. He therefore founded Health and Development International (HDI) in 1990, with one arm each in Norway and the United States to be able to work with larger groups there. Among other things, HDI started the effort to distribute filter straws in every country where Guinea worm existed. Several groups, both in Norway and the US, banded together to combat the disease. And it worked. In 2016, 25 people in three countries experienced Guinea worm, compared with 3.5 million 30 years ago.

The country doctor was ready for a new challenge.

Photo © Health and Development International

– We had – almost – managed to eradicate Guinea worm, against which there is no medicine and which was of no personal interest to political elites in poor or rich countries. We had done this in spite of civil wars, military dictatorships, and corruption. The question arose: What if we work in the same way as we do against Guinea worm, against something that is not biologically eradicable? Would we achieve the same results? In late 2003, HDI’s American board of directors was meeting. A new board member, a recent American ambassador to Niger, asked if it had to be a disease, could one rather choose a condition? And then she described obstetric fistula. I had hardly heard of it.

Obstetric fistulas occur if the baby’s head is stuck during birth. Pressure from the child’s skull against the pelvis causes tissue to die. That creates a hole, so urine and/or faeces leak. In Norway, the baby is brought out by surgery, “a caesarean”.

Photo © Health and Development International

Only One Sunrise

The methods are simple and effective: No woman must experience more than one sunrise while giving birth. Before sunrise number two, she must have help to get the baby out. Village volunteers must know this. They may not be able to read or write, but they can keep track of sunrise.

HDI’s aim is that interventions should be simple, and that existing resources should be used optimally: If there is a midwife and an ambulance, they should be used in the best ways possible. Women who already have a fistula are helped by HDI to the capital where they receive surgery.

– We work partly to spread information, partly with logistics, and partly with data collection. The data are analysed so we can find holes and weaknesses, Anders explains.

These data show that Niger has achieved 93% reduced maternal mortality in the pilot area. In the entire project area in Niger, mortality has been reduced by 88%. More than 100 000 women have given birth since last a woman died of blocked childbirth, according to HDI’s numbers. Obstetric fistula is also gone from project areas.

An Honour

The Kavli Trust has been supporting Anders Seim’s work since 2009. That happened after he had made a presentation at a private foundation about his work to prevent obstetric fistula. Several months later, he received an email from then Chairman of the Board Reidar Lorentzen who wondered whether HDI might like to apply for funding. He happened to have been in the audience during the presentation. The Kavli Trust has been on the team since then. Most recently with an extra grant to buy tablets that prevent women from bleeding too much after giving birth.

In 2000 Anders stopped practicing medicine in Fagerstrand. Now he works only at HDI. So, what does he get out of working on public health in Niger?

– It is nice to be useful, and when one has landed in a situation where one, literally, may enter both the most grandiose rooms and places where one must crawl on the ground to enter a home on a dusty plain, it is an honour. It gives a feeling of living life.

– Also, one cannot avoid asking whether it is absolutely necessary to let another 14 million women die while we wait for midwives to be educated, for corruption to be ended, for a functioning health service – have we no choice? Must we sit helplessly by, or can we change something by using modest funds? If the answer is we can, then I think we should.